Links.

Links.

Booker Prizes.

Booker Prizes.

Chocolate.

Chocolate.

Books read.

Books read.

Best books read in 2015.

Best books read in 2015.

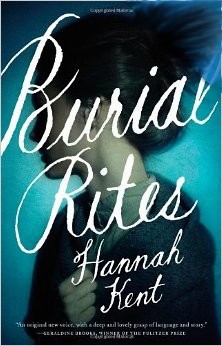

Best book read in 2014:

|

Hannah Kent's Burial Rites: a Novel (2013),

her first: a historical fiction set in Iceland.

Gripping and brilliant, it's set in the early nineteenth century,

in rural Iceland, where a woman accused of murder is temporarily housed at a farm as a servant.

Kent's plot, characters, and writing are all powerful and memorable.

Her structure is especially excellent,

interleaving historical documents and events

with her invented scenes and actions and conversations.

|

Best writers of poetry and prose

Best writers of poetry and prose

Harry Potter;

also Harry Potter en Español.

Harry Potter;

also Harry Potter en Español.

Why read a book?.

Why read a book?.

New books on Spirituality

by Pagels, Ehrman, et al.

New books on Spirituality

by Pagels, Ehrman, et al.

My chocolate of choice: